An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Challenges to Public Health Reporting Experienced by Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals, 2019

No. 56 | September 2021

- Challenges to Public Health Reporting Experienced by Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals, 2019 [PDF – 785.73 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Tables 2 and 3 [CSV – 829 bytes]

- Data Brief 56 Table A4 [CSV – 1.21 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Figure 1 [PNG – 48.85 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Figure 2 [PNG – 82.52 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Figure 3 Panel A [PNG – 131.86 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Figure 3 Panel B [PNG – 112.79 KB]

- Data Brief 56 Figure 3 Panel C [PNG – 96.66 KB]

Amidst a global pandemic, the need for efficient exchange of electronic health information between hospitals and public health agencies has never been more critical. To ensure public health agencies have timely and complete data to improve their disease surveillance capabilities, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has established policies that require hospitals to meet specific public health objectives as a condition for participation in the Promoting Interoperability (PI) program (1). These objectives include submission, and in some cases receipt of data, for the purposes of immunization registries, syndromic surveillance reporting, case reporting, and public health registry reporting. To understand the challenges hospitals faced with public health reporting in the year prior to the pandemic, this data brief uses nationally representative survey data from the 2019 American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) supplement to describe the number and types of challenges hospitals experienced when electronically reporting to public health agencies and how these challenges varied by state and hospital characteristics. While new challenges may have emerged or become exacerbated during the pandemic, this analysis identifies potential ongoing barriers to health information exchange among hospitals and public health agencies and provides insights into hospitals’ readiness to support key public health activities prior to the pandemic.

Highlights

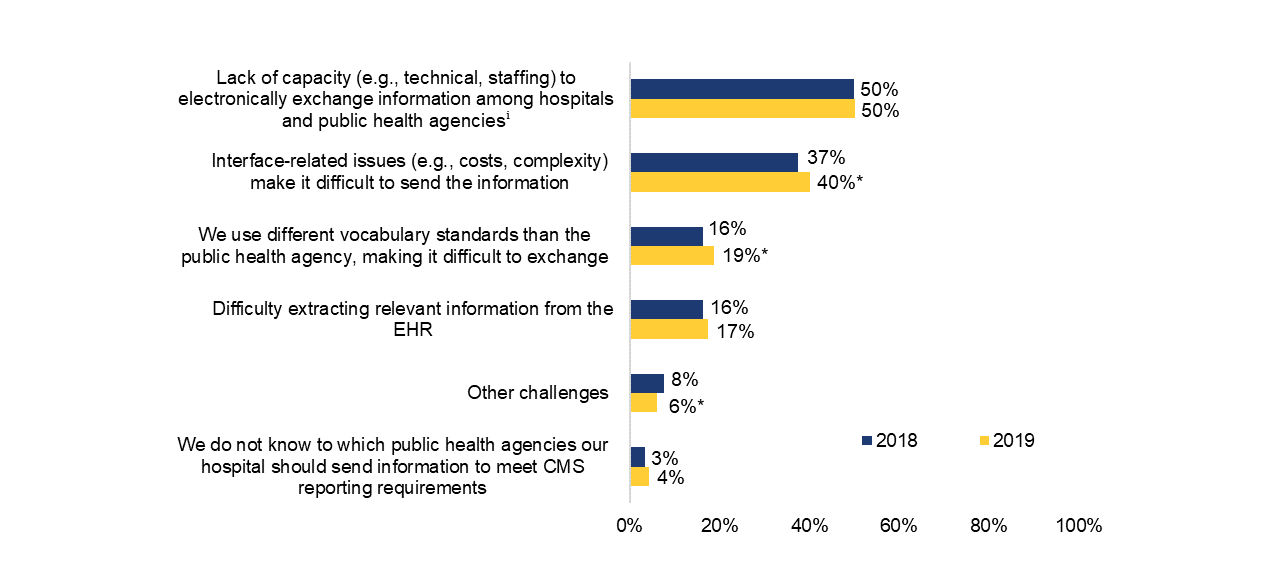

- In both 2018 and 2019, half of all hospitals reported a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information with public health agencies.

- In 2019, seven in ten hospitals experienced one or more challenges related to public health reporting.

- Small, rural, independent, and Critical Access hospitals were more likely to experience a public health reporting challenge compared to their counterparts.

- The types of public health reporting challenges experienced by hospitals varied substantially at the state-level.

Half of hospitals reported challenges related to electronically exchanging data with public health agencies

Findings

- Hospitals’ top two public health reporting challenges in both 2018 and 2019 included interface- related issues and a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information among hospitals and public health agencies.

- About one in five hospitals reported issues exchanging information due to differing vocabulary standards; a similar share of hospitals reported difficulty extracting relevant information from electronic health records (EHR).

- The percentage of hospitals experiencing public health reporting challenges related to interfaces and use of differing vocabulary standards grew slightly, yet significantly between 2018 and 2019

Figure 1: Types of challenges experienced by non-federal acute care hospitals, 2018-2019.

Note: Sample used for analyses includes non-federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the public health challenge questions. *Significantly different from previous year (p<0.05). Appendix Table A1 includes the original survey question and full description of public health reporting challenges.

ⁱ Refers to hospitals’ lack of capacity (e.g., technical, staffing) to electronically send information or public health agencies’ lack of capacity to electronically receive the information.

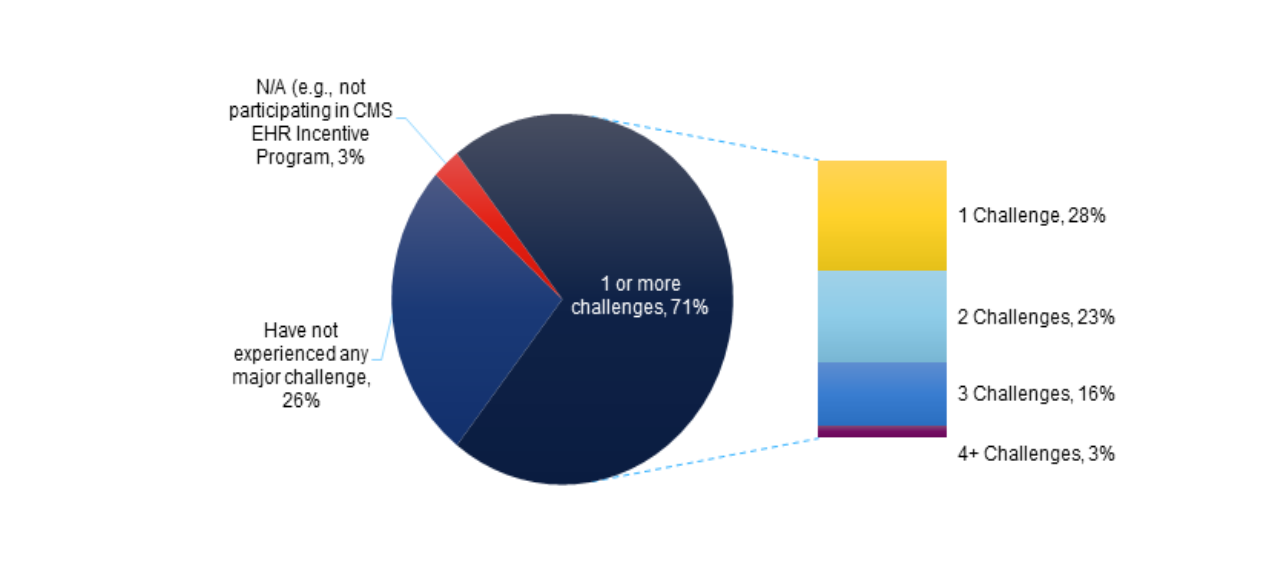

Seven in 10 hospitals experienced one or more challenges when electronically reporting to public health agencies in 2019.

Findings

- In 2019, the mean number of challenges hospitals experienced when reporting to public health agencies was 1.37 – this was similar to the number of challenges reported in 2018 (1.31) (Appendix Table A2).

- More than half of all hospitals nationally experienced one or two reporting challenges, while less than a quarter experienced three or more challenges.

- Among hospitals that reported only one public health reporting challenge, 60 percent said they experienced issues with either their own or public health agencies’ capacity to electronically exchange information and 21 percent experienced interface-related issues (Appendix Table A3).

- About a quarter of hospitals reported that they did not experience any major challenges related to public health reporting.

Figure 2: Number of challenges experienced by non-federal acute care hospitals, 2019.

Note: Sample used for analyses includes non-federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the public health challenge questions. Estimates may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

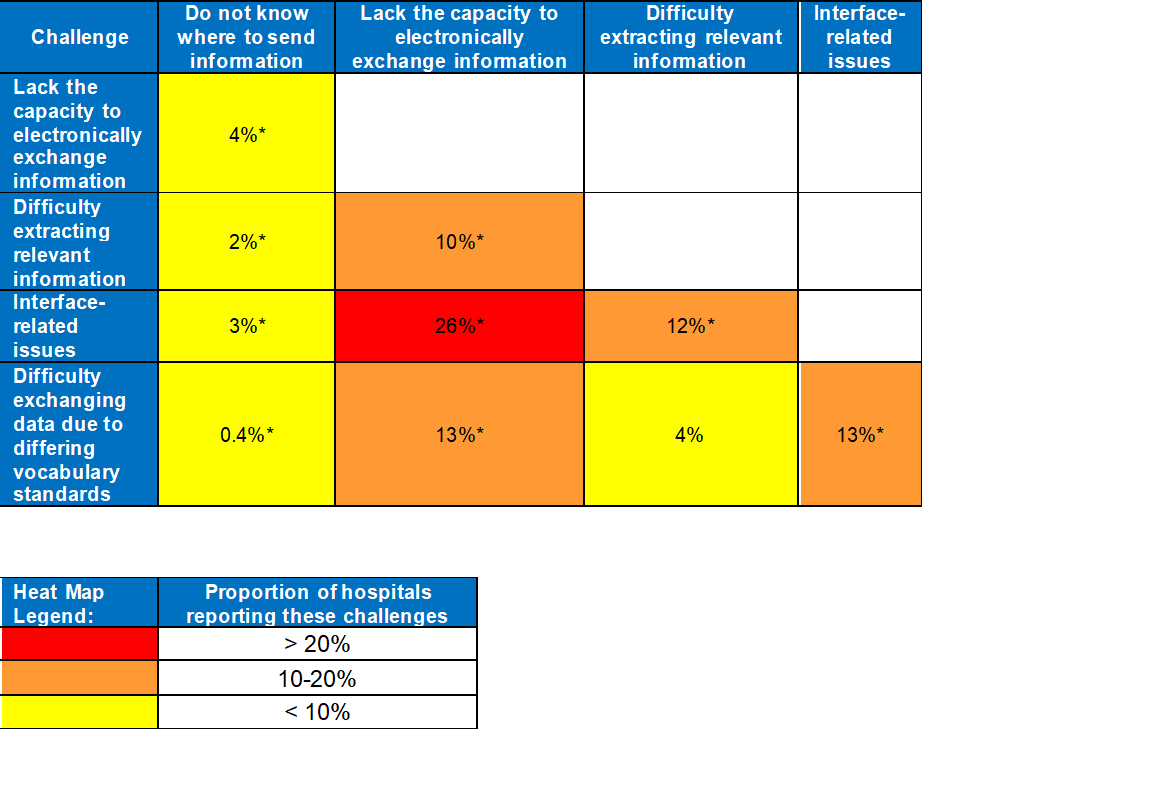

The most common public health reporting challenges hospitals experienced concurrently were issues with a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information and interface-related issues.

Findings

- About one in four hospitals (26%) reported experiencing both a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information (e.g., technical, staffing) and issues related to interfaces (e.g., costs, complexity) when reporting to public health agencies.

- Hospitals that experienced difficulties exchanging data due to differing vocabulary standards also experienced interface-related issues and a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information (13%, respectively).

- About one in 10 hospitals (12%) reported both interface-face related issues and difficulty extracting relevant information from the EHR.

Table 1: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that experienced multiple public health reporting challenges, 2019.

Notes: Sample used for analyses includes non-federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the public health challenge questions. *Significant association between challenges (p<0.05).

Small, rural, independent, and Critical Access Hospitals were more likely to experience one or more public health reporting challenges compared to their large and urban counterparts.

Findings

- Small, rural, independent, and Critical Access Hospitals (CAH) were more likely to report interface related issues, difficulty extracting relevant information from the EHR, and confusion about where to send information to meet reporting requirements compared to their counterparts.

- Issues related to a lack of capacity to electronically exchange information were common across hospitals – the share of hospitals experiencing this challenge did not differ significantly across hospital characteristics.

Table 2: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that experience public health reporting challenges by hospital, 2019

| Hospital Characteristics | Do not know where to send information (%) | Lack Capacity (%) | Difficulty extracting relevant information (%) | Interface-related issues (%) | Different vocabulary standards (%) | One or more challenges (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (50.3%) | 6.3 | 49.5 | 20 | 41.8 | 14.9 | 73.5 |

| Medium-Large (49.7%) | 2.3 | 50.8 | 14.7 | 38.4 | 22.8 | 68.7 |

| Critical access hospital (CAH) (28.6%) | 7.8 | 49.6 | 23.2 | 44 | 10.3 | 74.2 |

| Non-CAH (71.4%) | 2.9 | 50.3 | 15 | 38.5 | 22.3 | 69.9 |

| Rural (40.3)% | 6.4 | 48.4 | 21.1 | 44.4 | 12.9 | 74.8 |

| Suburban-Urban (59.7%) | 2.9 | 51.3 | 14.9 | 37.1 | 22.9 | 68.7 |

| Independent (33.3%) | 6.5 | 47.8 | 25.2 | 43.9 | 12.6 | 74.5 |

| System Affiliation (66.7%) | 3.2 | 51.3 | 13.5 | 38.2 | 22 | 69.5 |

Hospital participation in a health information exchange is associated with a lower probability of experiencing certain public health reporting challenges.

Findings

- Adjusting for hospital characteristics, hospitals that participate in a state, regional, or local health information exchange (HIE) are less likely to experience “difficulty extracting relevant information” from the EHR compared to those who do not participate in an HIE.

- Adjusting for hospital characteristics, hospitals that participate in an HIE are less likely to report that they “don’t know where to send information” compared to hospitals that do not participate in an HIE.

- Hospital participation in HIEs was not associated with public health reporting challenges related to either lack of capacity or interface related issues when adjusting for hospital characteristics.

Table 3: Predicted probabilies of experiencing different public health reporting challenges by HIE participation, 2019.

| Hospital Characteristics | Do not know where to send information (%) | Lack Capacity (%) | Difficulty extracting relevant information (%) | Interface-related issues (%) | Different vocabulary standards (%) | One or more challenges (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIE Participation: Do not participate in state, regional, or local HIE (22.6%) | 6.3 | 54.6 | 24.5 | 39 | 17.4 | 72.6 |

| HIE Participation: Participate in state, regional, or local HIE (77.4%) | 3.8 | 50.7 | 15.6 | 38.3 | 16.5 | 69.7 |

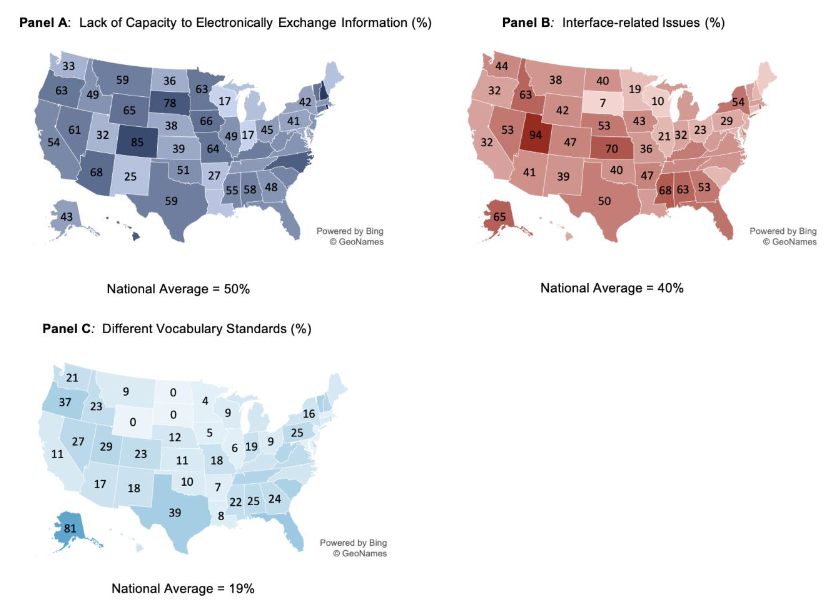

Public health reporting challenges vary substantially by state.

Findings

- Half of all hospitals nationally reported issues with the capacity to electronically exchange information; state estimates ranged from 17 percent to 100 percent.

- Four in ten hospitals experienced interface-related issues; state estimates ranged from seven percent to 94 percent.

- Less than one in five hospitals experienced difficulties exchanging health information due to different vocabulary standards; state estimates ranged from zero to 81 percent, respectively.

Figure 3: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that experienced public health reporting challenges by state, 2019.

Summary

Understanding the number and types of challenges experienced by hospitals with respect to public health reporting is critical to developing solutions aimed at improving hospital and public health agency capacity to effectively exchange health information. This data brief shows that just prior to the pandemic a majority of hospitals (71%) experienced public health reporting challenges that could impact public health agencies’ ability to monitor and respond to disease outbreaks. These findings are consistent with 2017 and 2018 survey findings, suggesting these were not emergent issues (2, 3). Among these challenges, lack of capacity to electronically exchange information (50%) and issues related to interfaces (40%) were most commonly reported by hospitals. Additionally, about one in five hospitals reported difficulties extracting relevant health information from their EHR (17%) and challenges exchanging information due to differing vocabulary standards (19%).

The types of challenges experienced by hospitals varied widely by geographic location. For instance, the share of hospitals experiencing interface-related issues ranged from seven to 94 percent whereas the share of hospitals experiencing difficulties exchanging information due to differing vocabulary standards ranged from zero to 81 percent. In states where a high percentage of hospitals experienced a public health reporting challenge, hospitals and public health agencies may need to work together to alleviate those issues. Addressing state level variation in reporting challenges will be critical to ensuring states have the capacity to exchange public health information. Efforts to create modern and interoperable public health systems are currently underway through the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative (DMI), which provides funding to state and local jurisdictions to invest in public health infrastructure and data modernization activities—e.g., syndromic surveillance, electronic case reporting (eCR), electronic lab reporting (eLR)—that facilitate data sharing across health systems (4).

In addition to state variation, we also found significant differences in the number and types of challenges experienced by hospital characteristics. Small, rural, independent, and Critical Access hospitals were significantly more likely to report interface related issues, difficulty extracting relevant information, and confusion about where to send information compared to their large and urban counterparts. These findings are consistent with previous data briefs examining variation in hospitals’ ability to electronically exchange health information by hospital characteristics (5, 6).

The challenges highlighted in this brief suggest there is a need to improve the methods hospitals use to electronically exchange health information with public health agencies. Adjusting for hospital characteristics, we found that hospitals participating in HIEs were less likely to report difficulties extracting relevant information from an EHR or not knowing where to send information. While it is possible that hospitals experiencing issues with data extraction and reporting were less likely to connect to HIEs, our findings suggest that HIE participation may be helpful in mitigating certain public health reporting challenges. Studies have shown that HIEs can support hospitals and public health agencies by addressing gaps in missing information, supporting public health reporting and monitoring, and providing other data services to help enable exchange (7-11). In September 2020, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) awarded funding through the Strengthening the Technical Advancement and Readiness of Public Health via Health Information Exchange Program (STAR HIE Program) to engage HIEs to support public health agencies and communities disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic (12). The STAR HIE program seeks to leverage HIEs to develop sustainable solutions that equip public health agencies to respond to future and ongoing public health emergencies and provide services for vulnerable and at-risk populations.

The ONC Cures Act Final Rule, published in May 2020, introduced two new technical certification criteria, Electronic Health Information Export and Standardized API for Patient and Population Services to improve exchange of electronic health information using certified health IT systems (13). While both of these certification criteria are intended to facilitate patients’ access to their health information and interoperability among clinicians, these functionalities can also support public health reporting (14, 15).

Examining hospitals’ experiences with public health reporting in the year prior to the pandemic sheds light on the different barriers faced by hospitals that may have limited their ability to effectively exchange information with public health agencies. However, it should be noted that variation in the number or types of challenges reported by hospitals may reflect underlying differences in rates of electronic public health reporting. For example, as more hospitals engage in electronic public health reporting they may experience more challenges (as compared to hospitals that don’t engage in these activities). Additionally, this work represents only hospitals’ perspectives. Future research should examine public health agencies’ perspectives on barriers to health information exchange. Understanding both hospitals’ and public health agencies’ experiences with sending and receiving public health data is critical to improving their ability to exchange. Another area that warrants greater investigation are hospital capabilities to perform specific types of public health reporting, including the methods used to facilitate exchange with state, local, and federal public health agencies. This could provide insights regarding the role of EHR developers, HIEs, and other entities actively involved in facilitating exchange. Collectively, these insights can help identify and prioritize areas for improvement in public health reporting so that public health agencies are well-positioned to respond to future public health emergencies.

Definitions

Application program Interface (API): APIs are technology that allow one software program to access the services provided by another software program. Note: Software programs could include web-based applications or mobile apps.

Critical Access hospital (CAH): Hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital.

Health information exchange (HIE): State, regional, or local health information network. This does not include local proprietary or enterprise networks.

Lack of capacity: Hospitals’ perceived lack of capacity to electronically exchange information with public health agencies. This composite measure reflects hospitals’ experiences with two public health reporting challenges (see Appendix Table A1): hospitals’ (self-reported) lack of capacity to electronically send information and public health agencies’ lack of capacity to electronically receive information (from the perspective of hospital respondents). Hospitals were said to experience challenges related to a lack of capacity to exchange information with public health agencies if they indicated one or both of these challenges.

Non-federal acute care hospital: Hospitals that meet the following criteria: acute care general medical and surgical, children’s general, and cancer hospitals owned by private/not-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Public Health Agency: State and local public health agencies support interoperability efforts and data exchange with electronic health records, many of which have been utilized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Promoting Interoperability Programs.

Rural hospital: Hospitals located in a non-metropolitan statistical area.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or less.

System Affiliated Hospital: A system is defined as either a multi-hospital or a diversified single hospital system. A multi-hospital system is two or more hospitals owned, leased, sponsored, or contract managed by a central organization. Single, freestanding hospitals may be categorized as a system by bringing into membership three or more, and at least 25 percent, of their owned or leased non-hospital pre-acute or postacute health care organizations.

Data Source and Methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey. Since 2008, ONC has partnered with the AHA to measure the adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ONC funded the 2019 AHA IT Supplement to track hospital adoption and use of EHRs and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or secure online site. Nonrespondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

The survey was fielded from the beginning of January 2020 to the end of June 2020. The response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals was 59 percent. The dataset was restricted to hospitals that answered the question about challenges experienced when submitting health information to public health agencies, resulting in a sample of 2,606 hospitals. A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Promoting Interoperability Certified EHR Technology. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/TableofContents_EH_Medicare_2019.pdf

2. Holmgren, A. J., Apathy, N. C., & Adler-Milstein, J. (August 2020). Barriers to hospital electronic

public health reporting and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(8), 1306-1309. 3. Walker, D. M., Yeager, V. A., Lawrence, J., & Mcalearney, A. S. (2021). Identifying Opportunities to Strengthen the Public Health Informatics Infrastructure: Exploring Hospitals’ Challenges with Data Exchange. The Milbank Quarterly.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Modernization Initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/data-modernization/php/about/dmi.html

5. Pylypchuk Y., Johnson C., Patel V. (March 2020). State of Interoperability and Methods Used for Interoperable Exchange among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2018. ONC Data Brief, no.51. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

6. Pylypchuk Y., Johnson C., Henry J. & Ciricean D. (November 2018). Variation in Interoperability among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2017. ONC Data Brief, no.42. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

7. Dixon, B. E., Zhang, Z., Arno, J. N., Revere, D., Joseph Gibson, P., & Grannis, S. J. (2020). Improving Notifiable Disease Case Reporting Through Electronic Information Exchange– Facilitated Decision Support: A Controlled Before-and-After Trial. Public Health Reports, 135(3), 401-410.

8. Dixon, B. E., McGowan, J. J., & Grannis, S. J. (2011). Electronic laboratory data quality and the value of a health information exchange to support public health reporting processes. In AMIA annual symposium proceedings (Vol. 2011, p. 322). American Medical Informatics Association.

9. Holmgren, A. J., Patel, V., & Adler-Milstein, J. (2017). Progress in interoperability: measuring US hospitals’ engagement in sharing patient data. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1820-1827.

10. Revere, D., Hills, R. H., Dixon, B. E., Gibson, P. J., & Grannis, S. J. (2017). Notifiable condition reporting practices: implications for public health agency participation in a health information exchange. BMC public health, 17(1), 1-12.

11. Walker, D. M., & Diana, M. L. (2016). Hospital adoption of health information technology to support public health infrastructure. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 22(2), 175-181.

12. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Strengthening the Technical Advancement & Readiness of Public Health via Health Information Exchange Program (The STAR HIE Program). https://healthit.gov/interoperability/investments#past-investments

13. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ONC’s Cures Act Final Rule. https://healthit.gov/regulations/cures-act-final-rule/

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (February 2021). eCR Now: COVID-19 Electronic Case Reporting for Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/hcp/electronic-case-reporting.html

15. Jones, J., Gottlieb, D., Mandel, J. C., Ignatov, V., Ellis, A., Kubick, W., & Mandl, K. D. (2021). A landscape survey of planned SMART/HL7 bulk FHIR data access API implementations and tools. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(6), 1284-1287.

Acknowledgements

The authors are with the Office of Technology, within the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. The data brief was drafted under the direction of Mera Choi, Director of Technical Strategy and Analysis, Talisha Searcy, Deputy Director of Technical Strategy and Analysis, and Vaishali Patel, Branch Chief of the Data Analysis Branch.

Suggested Citation

Richwine C., Marshall, C., Johnson C., & Patel, V. (September 2021). Challenges to Public Health Reporting Experienced by Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals, 2019. ONC Data Brief, no.56. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

Appendix Table A1: Survey question assessing public health reporting challenges experienced by hospitals

| Question Text | Response Options |

|---|---|

| 2019 AHA IT Supplement: What are some of the challenges your hospital has experienced when trying to submit health information to public health agencies to meet CMS reporting requirements for Promoting Interoperability Program? (Please check all that apply). |

|

| 2018 AHA IT Supplement: What are some of the challenges your hospital has experienced when trying to submit health Information to public health agencies to meet meaningful use requirements? (Please check al l that apply) |

|

Note: Response options b. and c. were combined to reflect a perceived lack of capacity to electronically exchange information among hospitals and/or public health agenices. Issues related to capacity to exchange information refers to hospitals’ lack of capacity to electronically send information to public health agencies and/or public health agencies’ lack of capacity to electronically receive the information.

Appendix Table A2: Mean Number of Public Health Reporting Challenges Experienced by Hospitals, 2018- 2019

| Year | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 1.31 | 1.14 |

| 2019 | 1.37 | 1.16 |

Notes: Sample used for analyses includes non-federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the public health challenge questions.

Appendix Table A3: Types of Challenges Hospitals Experienced by the Number of Challenges Reported, 2019

| Challenge Type | Number of Challenges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 challenge | 2 challenges | 3 challenges | 4 challenges | |

| Do not know where to send information | 1% | 5% | 11% | 35% |

| Issues with capacity to electronically exchange information | 60% | 64% | 93% | 98% |

| Difficulty extracting relevant information | 7% | 25% | 41% | 90% |

| Interface-related issues | 21% | 67% | 94% | 95% |

| Different vocabulary standards | 3% | 31% | 53% | 65% |

| Other | 8% | 7% | 7% | 25% |

Notes: Each column of this table shows the types of challenges hospitals experienced by the number of challenges they reported. Sample used for analyses includes non-federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the public health challenge questions.

Appendix Table A4: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that experienced public health reporting challenges by state, 2019

| State | Issues with capacity to electronically exchange information (%) | Interface challenges (%) | Different vocabulary standards than public health agencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AK | 43.22 | 64.99 | 81.46 |

| AL | 57.71 | 62.55 | 24.91 |

| AR | 26.6 | 47.28 | 6.83 |

| AZ | 68.32 | 41.02 | 16.97 |

| CA | 53.89 | 31.94 | 11.29 |

| CO | 85.35 | 46.53 | 22.99 |

| CT | 64.21 | 19.13 | 10.05 |

| DC | 48.06 | 17.04 | 17.04 |

| DE | 44.28 | 44.28 | 18.68 |

| FL | 51.43 | 55.84 | 44.39 |

| GA | 48.16 | 53.06 | 23.55 |

| HI | 76.77 | 27.92 | 14.95 |

| IA | 66.47 | 43.16 | 5.45 |

| ID | 48.83 | 62.91 | 22.58 |

| IL | 49.43 | 20.93 | 5.51 |

| IN | 17.44 | 31.64 | 19.17 |

| KS | 38.55 | 70.14 | 10.5 |

| KY | 60.31 | 50.92 | 15.94 |

| LA | 24.63 | 35.11 | 7.64 |

| MA | 46.64 | 34.37 | 3.92 |

| MD | 38.34 | 24 | 5.57 |

| ME | 25.92 | 11.7 | 11.59 |

| MI | 26.7 | 35.8 | 13.13 |

| MN | 62.85 | 18.65 | 4.05 |

| MO | 63.93 | 36.4 | 17.99 |

| MS | 55.12 | 68.01 | 22.06 |

| MT | 59.24 | 37.82 | 9.11 |

| NC | 75.17 | 38.83 | 13.97 |

| ND | 36.28 | 40.36 | 0 |

| NE | 38.39 | 52.5 | 12.11 |

| NH | 94.01 | 21.67 | 29.06 |

| NJ | 48.73 | 24.69 | 1.92 |

| NM | 25.4 | 38.99 | 18.16 |

| NV | 60.7 | 52.76 | 26.82 |

| NY | 41.89 | 54.17 | 15.87 |

| OH | 44.59 | 23.22 | 8.96 |

| OK | 51.02 | 39.94 | 9.79 |

| OR | 62.96 | 32.12 | 37.12 |

| PA | 41.45 | 28.52 | 25.09 |

| RI | 100 | 61.04 | 21.82 |

| SC | 56.77 | 21.28 | 35.93 |

| SD | 78.24 | 7.01 | 0 |

| TN | 46.17 | 44.15 | 32.19 |

| TX | 59.4 | 49.97 | 39.37 |

| UT | 32.21 | 94.37 | 29.26 |

| VA | 48.72 | 40.15 | 24.39 |

| VT | 65.78 | 34.04 | 34.04 |

| WA | 32.69 | 44.13 | 20.84 |

| WI | 17.42 | 10.15 | 9.04 |

| WV | 51.04 | 35.38 | 30.12 |

| WY | 65.13 | 42.24 | 0 |

Note: Sample used for analyses includes non -federal acute care hospitals only and excludes 72 hospitals (1.6%) that didn’t respond to any of the PH challenge questions. Percentages reflect hospitals that responded to the survey. Five states (AK, DC, DE, RI, VT) had fewer than 10 respondents which could impact the reliability of their estimates.