An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Electronic Capabilities for Patient Engagement among U.S. Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2013-2017

No. 45 | April 2019

The Medicare and Medicaid Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Programs incentivized hospitals to provide patients access to their health information through the use of certified EHR technology. Since 2014, eligible hospitals were required to provide patients with the capability to view, download, and transmit (VDT) their health information (1). VDT capability provides patients with electronic access to their personal health information. Other electronic patient engagement capabilities allow hospitals and their patients to interact online. This data brief explores the trends and variation in hospitals’ adoption of VDT and other electronic patient engagement capabilities.

Highlights

- In 2017, nearly all hospitals provided patients with the ability to electronically view and download their health information.

- Significantly fewer critical access hospitals (CAHs) provided patients with the ability to VDT compared to non- CAHs.

- Most hospitals (62 percent) reported that fewer than 25 percent of their patients activated their access to their patient portal.

- Nearly 4 in 10 hospitals reported that patients could access their health information using an application that connects to the hospital’s EHR through an application programming interface (API).

- The percent of hospitals who provided patients access to their health information using an API did not vary by hospital type.

Nearly all hospitals provided patients with the ability to electronically view and download their health information in 2017.

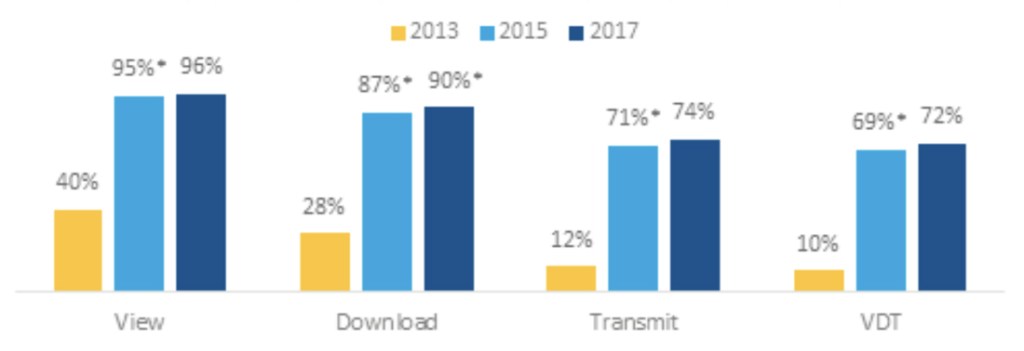

Figure 1: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals where patients are able to electronically view, download, and transmit their health information, 2013, 2015, and 2017.

NOTES: *Significantly different from previous two years (p<0.05). These data reflect hospital responses to questions regarding whether the hospital provides its patients with the ability to view, download and transmit their health information (see Definitions). These results may not be comparable to other industry measures of view, download and transmit.

- The percent of hospitals that provided patients with the ability to VDT increased seven-fold from 2013 to 2015. However, VDT rates did not significantly change from 2015 to 2017.

- In 2017, about 3 in 4 hospitals provided patients with the ability to transmit their health information.

CAHs were less likely than non-CAHs to provide patients with the ability to VDT their health information.

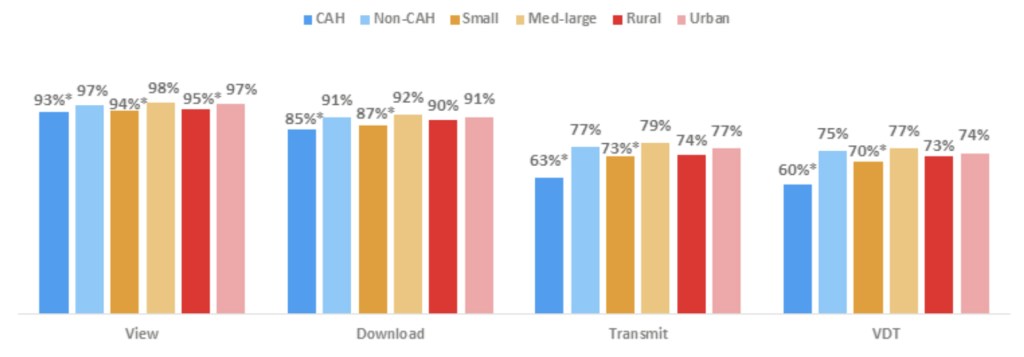

Figure 2: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals where patients are able to electronically VDT their health information by hospital type, 2017.

Notes: *Significantly different from its counterpart p<0.05). Critical Access hospitals are hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital. Small hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals with less than 100 beds. Med-large hospitals have >100 beds. Rural hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals in non-urban metropolitan areas.

- Although nearly all hospitals provided patients with the ability to view their health information, small, rural and CAHs lagged behind their counterparts by at least 2 percentage points.

- Hospitals where patients are able to download their health information did not vary significantly between rural (90 percent) and urban (91 percent) hospitals.

- About 5 percent fewer CAHs and small hospitals provided patients with the ability to download their health information compared to non-CAHs and medium and large hospitals, respectively.

- Compared to medium-large hospitals, fewer small hospitals provided patients with the ability to VDT (77 percent and 70 percent, respectively).

- CAHs and non-CAHs had the greatest difference, 15 percentage points, between hospital types that provided patients with the ability to VDT.

Nearly two-thirds of hospitals had fewer than 25 percent of patients activate access to the hospital’s patient portal in 2017.

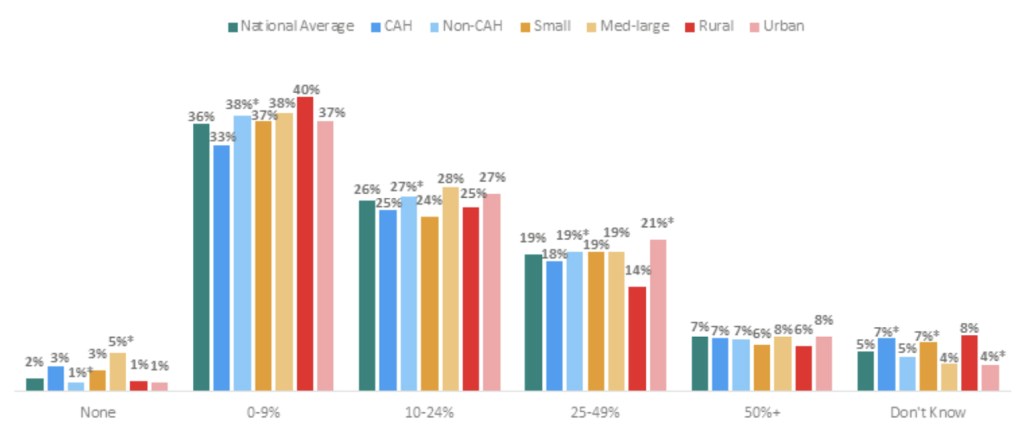

Figure 3: Percentage of patients who activated access to their patient portal by hospital type, 2017.

Notes: *Significantly different from its counterpart p<0.05). Critical Access hospitals are hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital. Small hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals with less than 100 beds. Med-large hospitals have >100 beds. Rural hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals in non-urban metropolitan areas. Approximately 4 percent of respondents are missing.

- Overall, few hospitals (8 percent or less) reported that 50 percent or more of patients activated access to their patient portal.

- On average, four in 10 hospitals reported that 0 to 9 percent of patients activated their patient portal.

- The proportion of rural hospitals (14 percent) that reported 25 to 49 percent of patients activated access to their patient portal, is significantly lower than the proportion of urban hospitals (21 percent); this indicated the greatest variation among hospital types.

- Compared to CAHs (33 percent), non-CAHs (38 percent) were more likely to report 0-9 percent of patients activated access to their patient portal.

- There were no significant differences between small and medium-large hospitals for the percent of patients who activated access to their patient portal, except for those who reported no patients activated their access to their patient portal.

In 2017, four in 10 hospitals reported offering their patients access to their health information using an application programming interface (API).

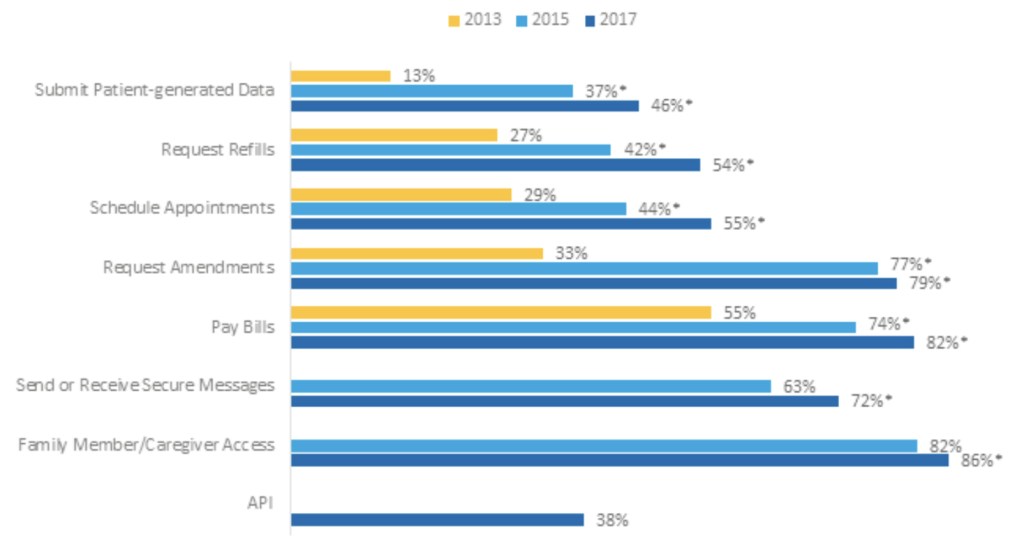

Figure 4: Electronic capabilities offered by non-federal acute care hospitals to their patients (excluding view, download, and transmit), by year, 2013, 2015, and 2017.

Notes: *Significantly different from previous 2 years (p<0.05). Family/Caregiver access and send or receive secure messages questions were added to the 2015 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement. API questions are new to the 2017 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

- In 2017, the capabilities most frequently available to patients were: family members or caregiver access on behalf of the patient (86 percent), pay bills online (82 percent), and request amendments to their health record (79 percent).

- Between 2013 and 2017 the percentage of hospitals that provided patients with the ability to request prescription refills and request amendments to their health records increased by 27 and 46 percent respectively.

- Between 2015 and 2017, the percent of hospitals that provided patients with the ability to request prescription refills electronically, increased by 12 percentage points to 54 percent.

- The percent of hospitals that provided patients with the ability to request amendments to their health record reported the smallest increase from 2015 to 2017 (2 percentage points).

- Hospitals that provided patients with the ability to submit patient generated data increased four-fold from 2013 to 2017.

In 2017, fewer CAHs, small, and rural hospitals offered patients electronic capabilities (excluding VDT) compared to their counterparts.

Table 1: The percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that offered electronic capabilities to their patients (excluding view, download, and transmit), by hospital type, 2017.

| API | Caregiver access | Request Amendments | Request Refills | Schedule Appointments | Pay Bills | Submit patient-generated Data | Send or Receive Secure Messages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | 38% | 81% | 72% | 48% | 42% | 75% | 36% | 66% |

| Urban | 37% | 90%* | 85%* | 58%* | 65%* | 86%* | 53%* | 76%* |

| Small | 39% | 82% | 73% | 49% | 44% | 76% | 39% | 68% |

| Med-Large | 36% | 90%* | 85%* | 58%* | 65%* | 87%* | 52%* | 76%* |

| CAH | 39% | 79% | 69% | 49% | 40% | 71% | 37% | 68% |

| Non-CAH | 37% | 89%* | 84%* | 55%* | 61%* | 86%* | 49%* | 73%* |

NOTES: *All values across row significantly different from category listed directly above (p<0.05). For example, all values across CAHs significantly different from non- CAHs. Critical Access hospitals are hospitals with less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital. Small hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals with less than 100 beds. Medium hospitals have between 100 and 399 beds. Large hospitals have 400 or more beds. Rural hospitals are all non-Critical Access hospitals in non-urban metropolitan areas.

- The percent of hospitals that provided patients access to their health information using an API did not vary by hospital type.

- Rural hospitals (36 percent) were less likely than urban hospitals to provide the capability for patients to submit patient-generated data.

- Nearly 90 percent of urban, medium-large, and non-CAHs offered family members or caregivers electronic access to a patient’s information; compared to 80 percent of rural, small, and CAHs.

- The capability to schedule appointments had the greatest variation among hospital types with difference of at least 21 percentage points between small, rural, and CAHS and their counterparts.

- Nine in 10 urban and medium-large hospitals, offered patients the capability to request amendments to their health record compared to 7 in 10 rural and small hospitals; which is lower than the national average (8 in 10).

Summary

To participate in the Medicare and Medicaid Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Programs, now renamed the Promoting Interoperability Program (PI), hospitals are required to use certified EHR technology. One aspect of program participation called for hospitals to provide patients with the ability to VDT their health information. In 2017, nearly all hospitals provided patients with the ability to electronically view and download their health information. In 2017, nearly 3 in 4 hospitals allowed patients to VDT their health information. From 2013 to 2017, the proportion of hospitals where patients are able to VDT increased seven-fold. Moreover, since 2015, the percent of hospitals that allowed patients to download their health information increased to 90 percent. However, other required functions (view and transmit) remained constant.

Hospitals’ possession of patient engagement capabilities varied by hospital type. A significantly lower percentage of CAHs provided patients with VDT capabilities. In 2017, 60 percent of CAHs compared to 75 percent of non-CAHs provided patients with VDT capabilities. Similarly, 70 percent of small hospitals provided patients with the ability to VDT compared to 77 percent of larger hospitals. There were no significant differences between rural and urban hospitals.

In 2017, the EHR Incentive Programs, required hospitals to provide 50 percent or more of its unique discharged patients with timely access to VDT their health information. Hospitals were also required to report whether patients acted to use this access (2). In 2017, almost two-thirds of hospitals reported that fewer than 25 percent of patients activated their access to the hospital’s patient portal. About 2 in 5 hospitals reported between 0 and 9 percent of patients accessed their health information through their patient portal. For 2019, the PI Program requires hospitals to report whether at least one unique discharged patient is provided timely access to VDT their health information to a third party or using an app (3).

Hospitals’ rates of patients accessing their patient portal also varied by hospital type. For example, compared to CAHs (33 percent), non-CAHs (38 percent) were more likely to report 0-9% of patients activated access to their patient portal. There was no significant difference between small and medium-large hospitals for the percent of patients who activated access to their patient portal. However, larger hospitals were more likely to report that no patients activated their access to their patient portal.

In addition to VDT, hospitals offered eight other electronic capabilities to their patients. In 2017, most hospitals (86 percent) allowed a family member or caregiver to access information on a patient’s behalf. Eight in 10 hospitals allowed patients to pay bills and request amendments to their health record. Additionally, the percent of hospitals that allowed patients to submit patient-generated data increased by four-fold between 2013 and 2017. However, CAHs, small, and rural hospitals offered patients fewer electronic capabilities compared to their counterparts. For example, rural and small hospitals were less likely to allow patients the capability to request amendments to their health record compared to their counterparts and the national average.

APIs can enhance patients’ access to their health information and improve how they engage with health care providers. Starting in 2019, hospitals participating in the PI Program must provide patients with the ability to use a third-party app of their choice to access their patient health information electronically. Prior ONC analysis revealed that 82% of hospitals have a vendor with products that meet the 2015 Edition API criteria available. We found that in 2017 38% of hospitals reported that patients can access their health information using an API (4).

Programs that encourage hospitals to provide these capabilities to patients are important to ensure that patients have their health information when and where they need it. A government-wide initiative, MyHealthEData, was launched by the White House Office of American Innovation that includes participation from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Veteran Affairs (VA), and ONC (5, 6). The goal of MyHealthEData is to break down the barriers patients experience with accessing their electronic health information and give them the power to determine where and how their health information is shared. ONC supports this initiative by continuing its work on advancing the availability of APIs through rulemaking to drive patient and clinician access to data (6). In addition, ONC has collaborated with the HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR) on the ONC Guide to Getting Your Health Records to educate patients on their Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-protected access right and how to get access to their online health records (7). Programs, like PI and MyHealthEData and collaborations with other federal offices, will encourage patients to access and use their data; hence helping the nation to achieve an interoperable system that empowers patients.

Definitions

Non-federal acute care hospital: Includes acute care general medical and surgical, children’s general, and cancer hospitals owned by private/not-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and District of Columbia.

View: Are patients treated in a hospital able to view their health/medical information online. Download: Are patients treated in a hospital able to download information from their health/medical record.

Transmit: Are patients treated in a hospital able to electronically transmit (send) transmission of care/referral summaries to a third party.

Interoperability: The ability of a system to exchange electronic health information with and use electronic health information from other systems without special effort on the part of the user (2). This brief further specifies interoperability as the ability for health systems to electronically send, receive, find, and use health information with other electronic systems outside their organization.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or less.

Medium-large hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or more.

Rural hospital: Located in a non-metropolitan statistical area.

Critical Access Hospital: Less than 25 beds and at least 35 miles away from another general or critical access hospital.

Application program Interface (API): APIs are technology that allow one software program to access the services provided by another software program. Note: Software programs could include web-based applications or mobile apps.

Data Source and Methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey. Since 2008, ONC has partnered with the AHA to measure the adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ONC funded the 2018 AHA IT Supplement to track hospital adoption and use of EHRs and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or secure online site. Non-respondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

The survey was fielded from January 2018 to the end of May 2018. The response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals was 64%. A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

References

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/regulations-guidance/promoting-interoperability-programs

2. EHR Incentive Programs in 2015 through 2017 Patient Electronic Access. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/2016_PatientElectronicAccess.pdf

3. Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program Eligible Hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals, and Dual-eligible Hospitals Attesting to CMS Objectives and Measures for 2019. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/MedicareEH_2019_Obj3.pdf

4. Posnack, Steve and Barker, Wes. (October 2018). Heat Wave: The U.S. is Poised to Catch FHIR in 2019. https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/interoperability/heat-wave-the-u-s-is-poised-to-catch-fhir-in-2019. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

5. MyHealthEData Initiative Press Release. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-announces-myhealthedata-initiative-put-patients-center-us-healthcare-system

6. Rucker, D., Health Affairs. June 2018. Achieving the Interoperability Promise Of 21st Century Cures. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/interoperability/achieving-the-interoperability-promise-of-21st-century-cures

7. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. The Guide to Getting & Using Your Health Records. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/how-to-get-your-health-record/

Acknowledgements

The authors are with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Office of Technology, Data Analysis Branch. The data brief was completed under the direction of Steve Posnack, Director of the Office of Technology and Talisha Searcy, Branch Chief Data Analysis Branch. Other staff that contributed to this document include: Lana Moriarty.

Suggested Citation

Henry J., Barker, W., & Kachay, L. (April 2019) Electronic Capabilities for Patient Engagement among U.S. Non-Federal Acute Care Hospitals: 2013-2017. ONC Data Brief, no. 45. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.